Long before fur traders, miners, and early settlers arrived in the area, the Columbia and Willamette rivers were regulated, highly utilized passageways that connected tribes throughout the region. These were the major arterials that made the shipment and trade of the region’s bounty possible. Highly trafficked and well-worn paths led down to the river’s edge, with many of these original Indian trails located where major thoroughfares exist today—most notably Sandy River Boulevard. These launch points were frequented by those wishing to trade or transport goods, people, and livestock and tolls were regularly charged for the convenience and privilege of utilizing safe and accessible launch points.

The influx of people descending on the region—early enterprisers such as the Hudson’s Bay fur trading company, explorers like Lewis and Clark, miners and treasure seekers, and migrants such as Americans from other states looking to move out West—had a profound impact on river utilization. Tribal sovereignty was disrupted and regulation over the waterways and what traveled down them began to unravel. In 1848, the Oregon Territory boundary was established. The original territory boundary included the land that would eventually become Washington State, with the Columbia River running horizontally through the middle of it.

Many people were interested in operating ferries along the river and for unique reasons: some wished to “cross” miners to the Indian trails to look for gold, some wished to shuttle livestock, some got in the business of transporting Oregon Trail settlers. All of this activity created economic opportunity (and opportunities to gouge ferry passengers with steep fares). In 1849, the newly formed Oregon Territory legislature passed “An Act Regulating Ferries” which granted licenses and set rates and taxes for would-be ferry operators. With this legislation came an untold number of applications for licenses. As the city of Portland was settled and growing into a bustling center for transport of freight along the Willamette valley, (with East Portland as its own city at the time), the need for ferry service crossing east and west along the river led to several ferry crossings whose notable names are recognizable to this day.

These enterprising new landowners saw a market and an opportunity to assist people across their land claims. For example, John Taylor, who owned a land claim along the Tualatin River, shuttled folks across his land for a toll. His passage was so heavily trafficked that, after years of operation, he built a bridge and a road to allow greater access for folks traveling into Portland. Taylors Ferry Road (along with Boones Ferry and Scholls Ferry Road) are lasting testaments to the impact that these early ferry operators had on the land development patterns throughout the region.

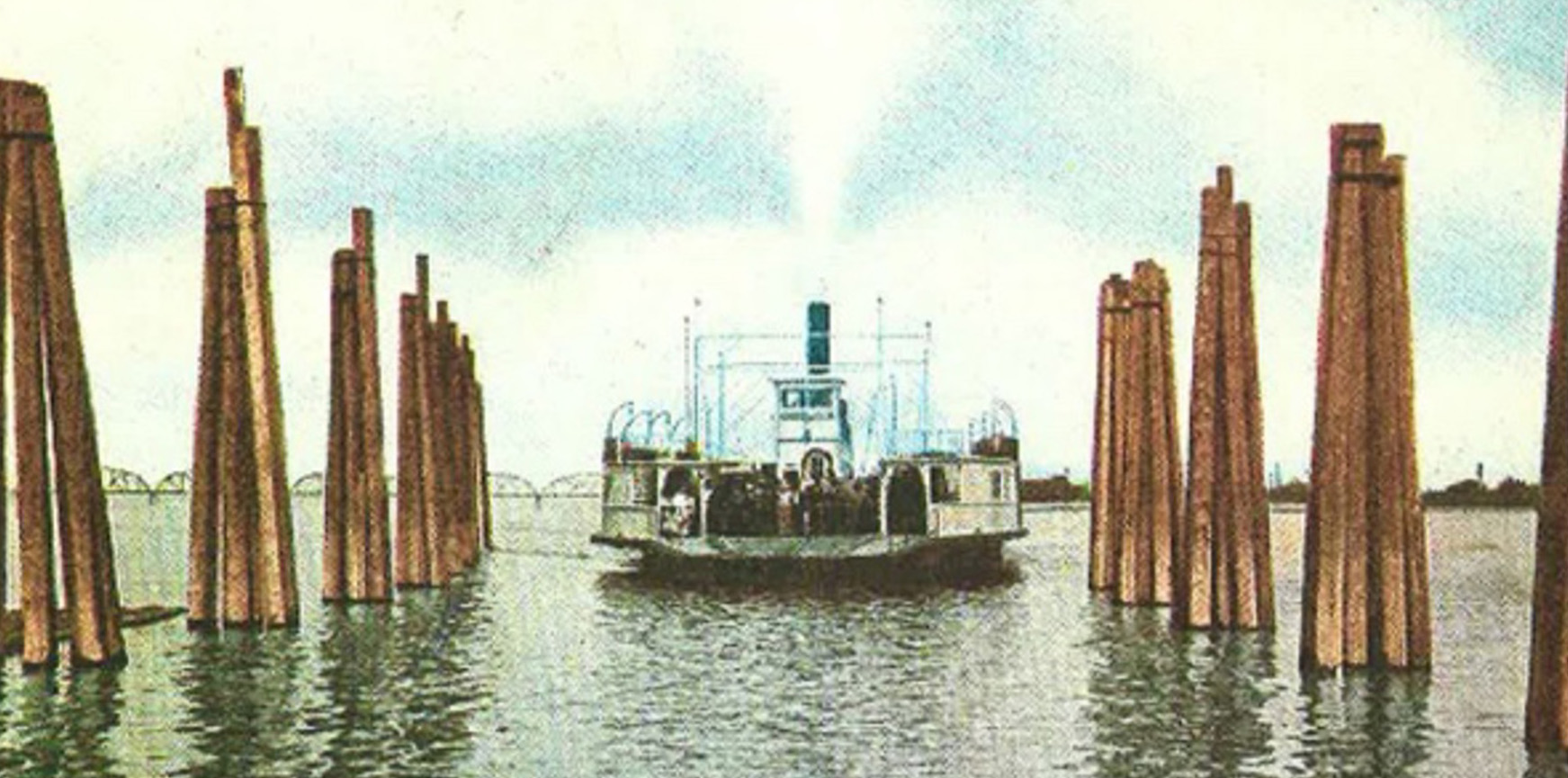

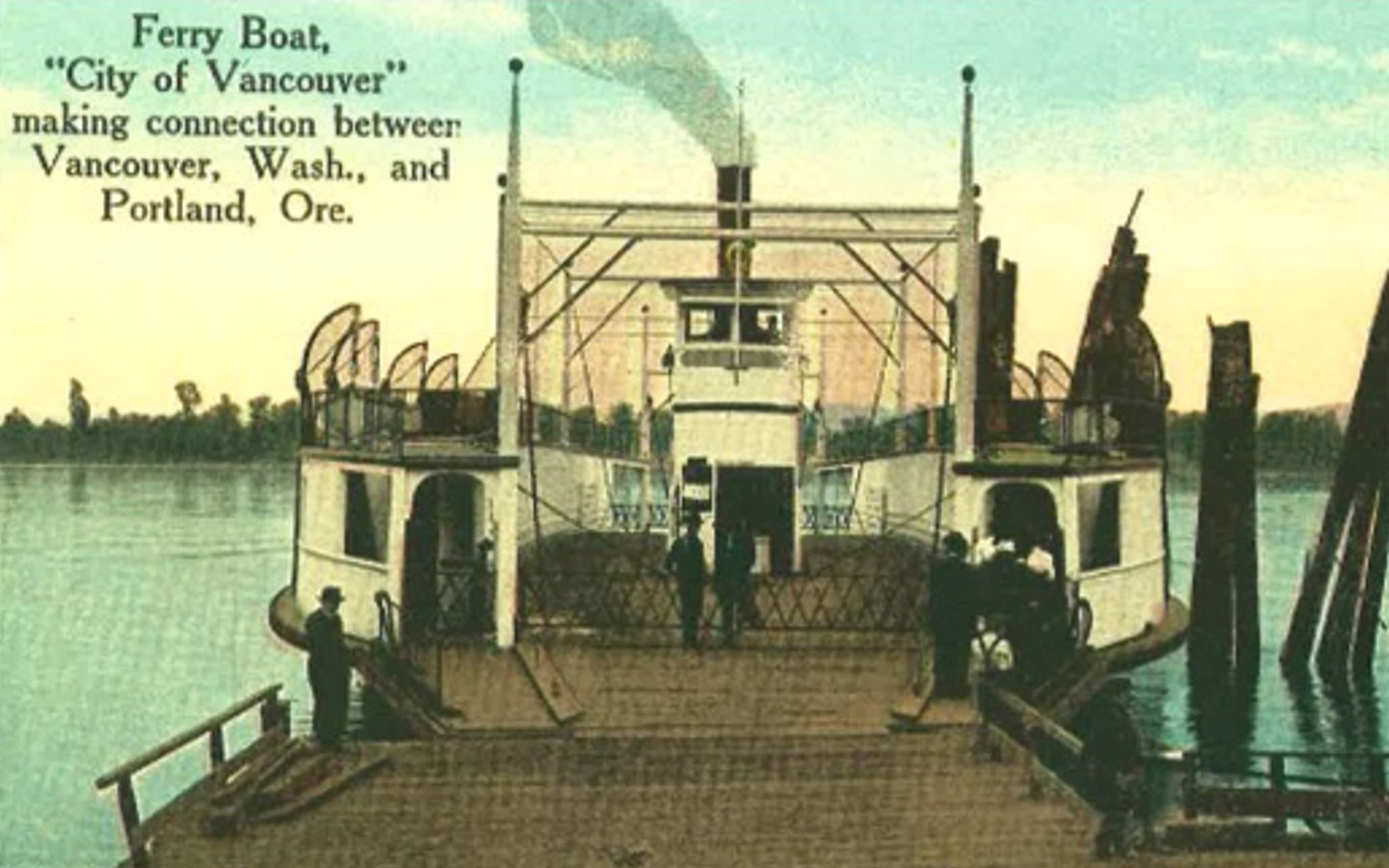

In addition to the smaller operators, Portland Railway Light & Power (PRL&P) played a heavy hand in large-scale ferry service between Portland and Vancouver. PRL&P was the local industrial monopoly that controlled all transportation facilities (and the still emerging electrical grid) in the Portland region. After 1853 when the Washington Territory made a break from the Oregon Territory, the Columbia River officially became the dividing boundary (and technically a federal highway) between the two territories, both of which would soon become states.

Governance and regulation over the Columbia River fell under the control of the PRL&P. This included the major ferry crossing that connected Vancouver and Portland. Originally, there were two railroad terminals in Portland and East Portland and along the north and south shores of the Columbia River. PRL&P was dependent on ferry crossing service to transport freight from one set of railcars to the other in order for goods to be fully transportable across the region. With the advent of the automobile and changing preferences by locals who wished for quicker ways of getting from ‘point A to point B,’ ferry service began to fall out of favor. PRL&P saw an opportunity to create an ‘interstate’ bridge that would allow rail freight to be moved at greater speed and efficiency. With strong public support, PRL&P underwrote the cost of the bridge. In 1917, the day that the new Interstate Bridge opened, Portland Railway Light & Power officially shut down ferry operations between Vancouver and Portland.

With public sentiment now wholly focused on automotive transportation, passenger ferry service effectively disappeared along the region’s waterways. What were once bustling, activated routes of transportation, the Columbia and Willamette rivers went dormant for most uses, save for occasional barge freight such as gravel and wheat, and occasional sightseers and pleasure boaters.

Authored by Allison Tivnon , Friends of Frog Ferry Board Member

Ruby, Brown. Ferry Boats on the Columbia River. Superior Publishing Company. 1974.

Charles F. Query. A History of Oregon Ferries since 1826. Maverick Publications. Revised 2008.